#5: How we do Feminist Economics

I (Alex) have spent much of the last month fretting over my upcoming presentation at the European Society of Translation Studies Congress in Leeds. It's been a whirlwind of powerpoints, business cards and consultations, but I've gradually realised that much of our presentation won't actually be about translation.

I'll be speaking on the subject of "Resisting Precarity: An Innovative Business and Governance Model for Language Workers", and in order to explain how we govern ourselves and do business in GMC, I'm going to have to give at least a brief primer on feminist economics. Since this is the beating heart of our collective, we've decided that it is something we want to share more widely, with the aim of fleshing it out more into a more complete blog article at some point, and in the hopes that other collectives might adopt this revolutionary way of creating value.

There's another, pro-commons element to this. Academic conferences are not accessible to non-academic folk, and the cost of attending a congress is prohibitive if you're not a student – the Leeds congress has cost us £350 just for entry alone – and it's essentially a form of gatekeeping. While we can't change this system, we want to make our work as publicly available as possible, so as well as writing this article, I'm going to record a separate video of our presentation (which I'll be rehearsing extensively) and upload it with the next edition of Textual Healing.

So what is Feminist Economics?

To understand Feminist Economics, we have to first accept that all work falls into two categories: productive and reproductive. Productive work is anything that "produces" money or income, and reproductive work is anything that does not directly create income, although it ensures the continuity of the whole system. The key here thing to understand here is that both kinds of labour have to happen – one cannot exist without the other. However, when it comes to distributing resources and recognition, they are anything but equal.

Feminist Economics is about recognising the unacknowledged, often invisible work that underpins the capitalist economy. Typically known as "care labour", this traditionally includes housework, cleaning and childcare, but it also extends to things like emotional labour and childbearing.

To take an obvious example, we can apply this lens to the traditional nuclear household, where the breadwinner goes out to work and provides money to support the household while their partner stays at home taking care of the house and children. Under traditional patriarchal economics, the breadwinner earns the right to control the household finances, while the care labour that makes it all possible is economically unrecognised.

Both productive and reproductive labour are equally essential to the household's survival, but according to our deeply entrenched social and gender norms, one person gets paid for their work and the other doesn't.

These values also govern how we see paid work. Care-based sectors like cleaning and childcare are exploitative and underpaid, but capitalist values also create the gender pay gap, and keep professions like sex work on the margins of economic society.

From an intersectional perspective, a similar dynamic plays out in the false dichotomy of skilled vs unskilled labour. Both are essential, but one is economically more valued than the other. It is no coincidence that a lot of care-based work is seen as both feminine and unskilled.

How we do Feminist Economics

Any profession has it share of productive and reproductive labour. Take teaching, for instance. A teacher is paid for a certain number of hours in the classroom, but they also have to plan classes, complete reports, mark homework, and so on. The class size is also not accounted for, nor is the time they spend commuting.

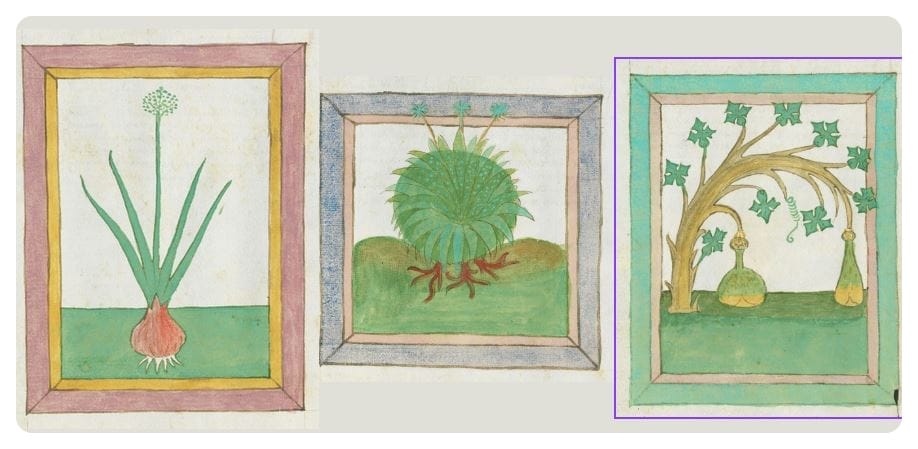

We've created a graphic representation of this in our own profession, which applies as much to us as it does to any freelance translator, editor or similar. What a client pays for is just the tip of the iceberg, but underneath it all there is a litany of unpaid care labour that someone has to do.

Our governance model recognises all of this work. Every second (including me writing this newsletter) is tracked and accounted for, and we are paid for it all at the end of the month. This means the reproductive work of emailing, correspondence and invoicing for a job is recognised on the same level as the person doing the productive work itself.

This extends to all areas that do not directly make money for the cooperative: time spent networking, posting on social media, seeking new clients, attending internal meetings, etc, etc, etc.

It also divides up the labour. If a client emails saying, for instance, "we need this 5000 word document translated by tomorrow", the translator is free to focus exclusively on the productive work, while other members are paid equitably to handle associated reproductive tasks and keep the coop ticking over without everything grinding to a halt.

A secret, third kind of labour

While our governance model is designed to equally recognise productive and reproductive work, it doesn't stop there. If you're reading this you'll probably be familiar with our pro-bono work, which we call Lovework. This is work that nobody pays us to do, but which we are paid to on an internal level through funds reserved from our income. So where does it fit into Feminist Economics?

Lovework is productive, in that it produces something (translations, usually), but also non-productive, in that it doesn't produce income for the collective nor it is guided by profit. It's also something we really do out of our love – for translation, for others, for ourselves. If Carework is the beating heart of our collective, Lovework was the original seed from which Guerrilla Media Collective sprang. With Lovework we get to choose where to allocate our resources, and make sure they're producing something worthwhile for people who otherwise wouldn't be able to afford good translation services.

Lovework is therefore a way for us to enact solidarity instead of charity. It provides something of value, both to the people whose work we translate and the world at large – all of our Lovework is released under a Creative Commons license, meaning it can be reproduced and republished ad infinitum.

Financial constraints mean that Lovework is currently confined to the work we publish on our blog, but it also covers the editing work in our Translators Against the Machine series, and the rewriting of our internal resources such as the handbook. It's a way for us to produce something on our own terms, without being hamstrung by the demands of creating income in a capitalist system.